Gregory Palamas

Gregory Palamas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Archbishop of Thessalonica and Pillar of Orthodoxy | |

| Born | 1296 Constantinople, (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Died | 14 November 1357/1359 Thessalonica, Theme of Thessalonica (modern-day Greece) |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Anglican Communion Byzantine Catholic Churches |

| Canonized | 1368, Constantinople by Patriarch Philotheos of Constantinople |

| Major shrine | Thessaloniki Theology career |

| Notable work | Philokalia |

| Theological work | |

| Tradition or movement | Palamism |

| Main interests | Asceticism, mysticism |

| Notable ideas | Essence–energies distinction, theosis, Tabor Light |

| Feast | 14 November, Second Sunday of Great Lent |

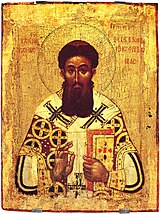

| Attributes | Long, tapering dark beard, vestments of a bishop, Gospel Book or scroll, right hand raised in benediction |

| Influenced | Nilus Cabasilas, Gennadius Scholarius, Nicodemus the Hagiorite, Sophrony of Essex, John Meyendorff, Seraphim Rose |

| Part of a series on |

| Palamism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

Gregory Palamas (/pæləˈmɑːs/; Greek: Γρηγόριος Παλαμᾶς [palaˈmas]; c. 1296 – 1357/1359)[1][2] was a Byzantine Greek theologian and Eastern Orthodox cleric of the late Byzantine period. A monk of Mount Athos (modern Greece) and later archbishop of Thessalonica, he is famous for his defense of hesychast spirituality, the uncreated character of the light of the Transfiguration, and the distinction between God's essence and energies (i.e., the divine will, divine grace, etc.). His teaching unfolded over the course of three major controversies, (1) with the Italo-Greek Barlaam between 1336 and 1341, (2) with the monk Gregory Akindynos between 1341 and 1347, and (3) with the philosopher Gregoras, from 1348 to 1355. His theological contributions are sometimes referred to as Palamism, and his followers as Palamites.

Gregory has been venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church since 1368. Within the Catholic Church, he has also been called a saint; Pope John Paul II repeatedly called Gregory a great theological writer.[3] Since 1971, the Melkite Greek Catholic Church has venerated Gregory as a saint.[4][5] Some of his writings are collected in the Philokalia, and since the Ottoman period, the second Sunday of Great Lent is dedicated to the memory of Gregory Palamas in most branches of the Eastern Orthodoxy, while in some, and in Eastern Catholic Churches, the issue is disputed.

Early life

[edit]Gregory was born in Constantinople around the year 1296. His father, Constantine, was a courtier of the Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos (1282–1328), but died when Gregory was still young. The Emperor himself took part in the raising and education of the fatherless boy and hoped that the gifted Gregory would devote himself to government service, but Palamas chose monastic life on Mt. Athos. Gregory's mother (Kalloni) and siblings (Theodosios, Makarios, Epicharis, and Theodoti) would also embrace monasticism, and the entire family was canonized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in 2009.

Before leaving for Mt. Athos, Gregory received a broad education at the University of Constantinople, including the study of Aristotle, which he would display before Theodore Metochites and the Emperor.[6]

Monastic life

[edit]Despite the Emperor's ambitions for him, Gregory, then barely 21 years old, withdrew to Mount Athos in the year 1316 and became a novice there in the Vatopedi monastery under the guidance of the monastic Elder St Nicodemos of Vatopedi. Eventually, he was tonsured a monk, and continued his life of asceticism. After the demise of the Elder Nicodemus, Gregory spent eight years of spiritual struggle under the guidance of a new Elder, Nicephorus. After this last Elder's repose, Gregory transferred to the Great Lavra of St. Athanasius the Athonite on Mount Athos, where he served the brethren in the trapeza (refectory) and in church as a cantor. Wishing to devote himself more fully to prayer and asceticism he entered a skete called Glossia, where he taught the ancient practice of mental prayer known as "prayer of the heart" or hesychasm.

In 1326, because of the threat of Turkish invasions, he and the brethren retreated to the defended city of Thessaloniki, where he was then ordained a priest. Dividing his time between his ministry to the people and his pursuit of spiritual perfection, he founded a small community of hermits near Thessaloniki in a place called Veria.

He served for a short time as Abbot of the Esphigmenou Monastery but was forced to resign in 1335 due to discontentment regarding the austerity of his monastic administration.[7]

Hesychast controversy

[edit]Hesychasm attracted the attention of Barlaam, a man who either converted to Orthodoxy or was baptized Orthodox[8][9] who encountered Hesychasts and heard descriptions of their practices during a visit to Mount Athos; he had also read the writings of Palamas, himself an Athonite monk. Trained in Western Scholastic theology, Barlaam was scandalized by hesychasm and began to combat it both orally and in his writings. As a private teacher of theology in the Western Scholastic mode, Barlaam propounded a more intellectual and propositional approach to the knowledge of God than the hesychasts taught.

On the hesychast side, the controversy was taken up by Palamas who was asked by his fellow monks on Mt Athos to defend hesychasm from the attacks of Barlaam. Palamas was well-educated in Greek philosophy. Gregory wrote a number of works in its defense and defended hesychasm at six different synods in Constantinople ultimately triumphing over its attackers in the synod of 1351.

Early conflict between Barlaam and Palamas

[edit]Although Barlaam came from southern Italy, his ancestry was Greek and he claimed Eastern Orthodoxy as his Christian faith. Arriving in Constantinople around 1330, Barlaam was working on commentaries on Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite under the patronage of John VI Kantakouzenos. Around 1336, Gregory received copies of treatises written by Barlaam against the Latins, condemning their insertion of the Filioque into the Nicene Creed. Although this condemnation was solid Orthodox theology, Palamas took issue with Barlaam's argument in support of it, namely that efforts at demonstrating the nature of God (specifically, the nature of the Holy Spirit) should be abandoned, because God is ultimately unknowable and undemonstrable to humans. Thus, Barlaam asserted that it was impossible to determine from whom the Holy Spirit proceeds. According to Sara J. Denning-Bolle, Palamas viewed Barlaam's argument as "dangerously agnostic". In his response titled "Apodictic Treatises", Palamas insisted that it was indeed demonstrable that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father but not from the Son.[10] A series of letters ensued between the two but they were unable to resolve their differences amicably.

Triads

[edit]In response to Barlaam's attacks, Palamas wrote nine treatises entitled "Triads For The Defense of Those Who Practice Sacred Quietude". The treatises are called "triads" because they were organized as three sets of three treatises.

The Triads were written in three stages. The first triad was written in the second half of the 1330s and are based on personal discussions between Palamas and Barlaam although Barlaam is never mentioned by name.[10]

Gregory's teaching was affirmed by the superiors and principal monks of Mt. Athos, who met in synod during 1340–1. In early 1341, the monastic communities of Mount Athos wrote the Hagioritic Tome under the supervision and inspiration of Palamas. Although the tome does not mention Barlaam by name, the work clearly takes aim at Barlaam's views. The tome provides a systematic presentation of Palamas' teaching and became the fundamental textbook for Byzantine mysticism.[11]

In response, Barlaam drafted "Against the Messalians", which attacked Gregory by name for the first time.[12] Barlaam derisively called the hesychasts omphalopsychoi (men with their souls in their navels) and accused them of the heresy of Messalianism, also known as Bogomilism in the East.[10][13] According to Meyendorff, Barlaam viewed "any claim of real and conscious experience of God as Messalianism".[14][15][16]

Barlaam also took exception to the doctrine held by the hesychasts as to the uncreated nature of the light, the experience of which was said to be the goal of hesychast practice, regarding it as heretical and blasphemous. It was maintained by the hesychasts to be of divine origin and to be identical to the light which had been manifested to Jesus' disciples on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration.[17] Barlaam viewed this doctrine of "uncreated light" to be polytheistic because as it postulated two eternal substances, a visible and an invisible God. Barlaam accuses the use of the Jesus Prayer as being a practice of Bogomilism.[18]

The second triad quotes some of Barlaam's writings directly. In response to this second triad, Barlaam composed the treatise "Against the Messalians" linking the hesychasts to the Messalians and thereby accusing them of heresy.

In the third Triad, Palamas refuted Barlaam's charge of Messalianism by demonstrating that the hesychasts did not share the antisacramentalism of the Messalians nor did they claim to physically see the essence of God with their eyes.[14] According to Fr. John Meyendorff "Gregory Palamas orients his entire polemic against Barlaam the Calabrian on the issue of the Hellenic wisdom which he considers to be the main source of Barlaam's errors."[19]

Role in the Byzantine civil war

[edit]Although the civil war between the supporters of John VI Kantakouzenos and the regents for John V Palaeologus was not primarily a religious conflict, the theological dispute between the supporters and opponents of Palamas did play a role in the conflict. Steven Runciman points out that "while the theological dispute embittered the conflict, the religious and political parties did not coincide."[20] The aristocrats supported Palamas largely due to their conservative and anti-Western tendencies as well as their links to the staunchly Orthodox monasteries.[21] Although several significant exceptions leave the issue open to question, in the popular mind (and traditional historiography), the supporters of "Palamism" and of "Kantakouzenism" are usually equated.[22][23] Thus, the eventual triumph of Kantakouzenos in 1347 also brought with it the conclusive triumph of the Palamists over the anti-Palamists.

Fifth Council of Constantinople

[edit]It became clear that the dispute between Barlaam and Palamas was irreconcilable and would require the judgment of an episcopal council. A series of six patriarchal councils were held in Constantinople on 10 June 1341, August 1341, 4 November 1344, 1 February 1347, 8 February 1347, and 28 May 1351 to consider the issues.[24] Collectively, these councils are accepted as having ecumenical status by Orthodox Christians,[25] some of whom call them the Fifth Council of Constantinople and the Ninth Ecumenical Council.

The dispute over hesychasm came before a synod held at Constantinople in May 1341 and presided over by the Emperor Andronicus III. The assembly, influenced by the veneration in which the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius were held in the Eastern Church, condemned Barlaam, who recanted. The ecumenical patriarch insisted that all of Barlaam's writings be destroyed and thus no complete copies of Barlaam's treatise "Against Messalianism" have survived.[10]

Barlaam's primary supporter Emperor Andronicus III died just five days after the synod ended. Although Barlaam initially hoped for a second chance to present his case against Palamas, he soon realised the futility of pursuing his cause, and left for Calabria where he converted to the Roman Church and was appointed Bishop of Gerace.[12]

After Barlaam's departure, Gregory Akindynos became the chief critic of Palamas. A second council held in Constantinople in August 1341 condemned Akindynos and affirmed the findings of the earlier council. Akindynos and his supporters gained a brief victory at a council held in 1344 which excommunicated Palamas. However, the last of these councils, held in May 1351, conclusively exonerated Palamas and condemned his opponents.[12] This synod ordered that the Metropolitans of Ephesus and Ganos be defrocked and jailed. All those who were unwilling to submit to the orthodox view were to be excommunicated and kept under surveillance at their residences. A series of anathemas were pronounced against Barlaam, Akindynos and their followers; at the same time, a series of acclamations were also declared in favor of Gregory Palamas and the adherents of his doctrine.[26] One notable opponent of Palamism was Nicephorus Gregoras who refused to submit to the dictates of the synod and was effectively imprisoned in a monastery for two years.

Gradual acceptance of the Palamist doctrine

[edit]

Kallistos I and the ecumenical patriarchs who succeeded him mounted a vigorous campaign to have the Palamist doctrines accepted by the other Eastern patriarchates as well as all the metropolitan sees under their jurisdiction. However, it took some time to overcome initial resistance to his teachings. For example, the Metropolitan of Kiev, upon receiving tomes from Kallistos that expounded the Palamist doctrine, rejected it vehemently and composed a reply in refutation. Similarly, the Patriarchate of Antioch remained steadfastly opposed to what they viewed as an innovation; however, by the end of the fourteenth century, Palamism had become accepted there. Similar acts of resistance were seen in the metropolitan sees that were governed by the Latins as well as in some autonomous ecclesiastical regions, such as the Church of Cyprus.[27]

One notable example of the campaign to enforce the orthodoxy of the Palamist doctrine was the action taken by Patriarch Philotheos I to crack down on Prochoros Kydones, a monk and priest at Mount Athos who was opposed to the Palamites. Kydones had written a number of anti-Palamist treatises and continued to argue forcefully against Palamism even when brought before the patriarch and enjoined to adhere to the orthodox doctrine. Finally, in exasperation, Philotheos convened a synod against Kydones in April 1368. However, even this extreme measure failed to effect the submission of Kydones and in the end, he was excommunicated and suspended from the clergy in perpetuity. The long tome that was prepared for the synod concludes with a decree canonizing Palamas who had died in 1357/59.[28]

Despite the initial opposition of some patriarchates and sees, over time the resistance dwindled away and ultimately Palamist doctrine became accepted throughout the Eastern Orthodox Church. During this period, it became the norm for ecumenical patriarchs to profess the Palamite doctrine upon taking possession of their see.[27]

Martin Jugie states that the opposition of the Latins and the Latinophrones, who were necessarily hostile to the doctrine, actually contributed to its adoption, and soon Latinism and Antipalamism became equivalent in the minds of many Orthodox Christians.[27]

According to Aristeides Papadakis, "all Orthodox scholars who have written on Palamas — Lossky, Krivosheine, Papamichael, Meyendorff, Christou — assume his voice to be a legitimate expression of Orthodox tradition."[29]

Later years

[edit]

Palamas's opponents in the hesychast controversy spread slanderous accusations against him, and in 1344 Patriarch John XIV imprisoned him for four years. However, in 1347 when Patriarch Isidore came to the Ecumenical Throne, Gregory was released from prison and consecrated as the Metropolitan of Thessalonica. However, since the conflict with Barlaam had not been settled at that point, the people of Thessalonica did not accept him, and he was forced to live in a number of places. It was not until 1350 that he was able to occupy the episcopal chair.[20] In 1354, during a voyage to Constantinople, the ship he was in fell into the hands of Turkish pirates; he was imprisoned and beaten. He was obliged to spend a year in detention at the Ottoman court where he was well treated.[20] Eventually his ransom was paid and he returned to Thessaloniki, where he served as archbishop for the last three years of his life.

Death and canonization

[edit]Palamas died in 1357 or 1359. His dying words were, "To the heights! To the heights!" He was canonized a saint of the Eastern Orthodox Church in 1368 by Patriarch Philotheos of Constantinople, who also wrote his Vita and composed the service which is chanted in his honour. His feast day is celebrated twice a year, on 14 November, the anniversary of his death, and on the Second Sunday of Great Lent, because Gregory's victory over Barlaam is seen as a continuation of the Triumph of Orthodoxy, i.e., the victory of the Church over heresy, celebrated the previous Sunday.

Gregory's relics rest in the Church of Saint Gregory Palamas in Thessaloniki.

Veneration in Eastern Slavic uses of Byzantine rite

[edit]The first printed Church Slavonic editions of the Triodion did not include the Sunday of Gregory Palamas[30] until liturgical reforms of Petro Mohyla[31] who, inter alia, aimed to update Kievan use of the Byzantine rite to then-contemporary version of its Greek counterpart. Mohyla's reforms inspired subsequent Nikon's reforms that brought liturgical veneration of Gregory Palamas to Moscow.

But the liturgical uses of communities that did not accept these reforms or were not affected by them, namely Old Believers and Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church, did not traditionally have this celebration.

A special case is Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, who was not affected by any of these reforms initially. But her main printing center in Kyiv was affected by Peter the First's censorship laws banning the use of any church books not conforming to Nikonian editions.[32] At the Synod of Zamość it was agreed to obey this policy,[32] but out of the new celebrations included in those books, only the office of Gregory Palamas was to be left out.[33] Since then, the question of rehabilitation of Gregory Palamas in the UGCC is sometimes raised,[34] and some English-speaking dioceses include him in their calendars[35] despite the ban of his veneration having never been lifted and official UGCC calendar not including his name.[36]

Hymns

[edit]O light of Orthodoxy, teacher of the Church, its confirmation,

O ideal of monks and invincible champion of theologians,

O wonder-working Gregory, glory of Thessaloniki and preacher of grace,

always intercede before the Lord that our souls may be saved.— Troparion (Tone 8)

Holy and divine instrument of wisdom,

joyful trumpet of theology,

together we sing your praises, O God-inspired Gregory.

Since you now stand before the Original Mind, guide our minds to Him, O Father,

so that we may sing to you: "Rejoice, preacher of grace."— Kontakion (Tone 8)

Works

[edit]- Patrologia Graeca, vols. 150, 151

- Philokalia

Primary works translated into English

[edit]- Chamberas, Fr. Peter A. (2021). St. Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessalonica - The Triads: In Defense of Those Who Practice Sacred Quietude. Translated by Fr. Peter A. Chamberas. Newfound Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7361-1671-5.

- The Triads (Classics of Western Spirituality Series) (ISBN 0-8091-2447-5)

- Philokalia, Volume 4 (ISBN 0-571-19382-X)

- Saint Gregory Palamas: The Homilies, (The Complete Homilies Translated into English - Published in 2009) (ISBN 0977498344)

- Homilies of Saint Gregory Palamas, Vol. 1 (ISBN 1-878997-67-X)

- Homilies of Saint Gregory Palamas, Vol. 2 (ISBN 978-1-878997-68-5)

- Treatise on the Spiritual Life (ISBN 1-880971-05-4)

- The One Hundred and Fifty Chapters (ISBN 0-88844-083-9)

- Dialogue Between an Orthodox and a Barlaamite (ISBN 978-1-883058-21-0)

See also

[edit]- Tabor Light

- Mount Athos

- Gregory Acindynus

- Christian mysticism

- The Ascetical Homilies of Isaac the Syrian, a 7th-century hesychastic text

References

[edit]- ^ Russell 2019, p. 1.

- ^ Rigo, A. (1989), "La vita e le opera di Gregorio Sinaita." Cristianesimo nella storia 10: 579–608.

- ^ Pope John Paul II, Homily at Ephesus, 30 November 1979, General Audience, 14 November 1990, General Audience, 12 November 1997, General Audience, 19 November 1997, Jubilee of Scientists

- ^ "The Search for Sacred Quietude". Newton, MA: Eparchy of Newton. 17 March 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Saint Gregory Palamas". Melkite Greek Catholic Church Information Center. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ John Meyendorff, A Study of Gregory Palamas, trans. George Lawrence (London: The Faith Press, 1964), pp. 28-41.

- ^ Archbishop Chrysostomos, Orthodox and Roman Catholic Relations from the Fourth Crusade to the Hesychastic Controversy (Etna, CA: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 2001), pp. 199‒232

- ^ The Ninth Ecumenical Council of 1341 condemned the Platonic mysticism of Barlaam the Calabrian who had come from the West as a convert to Orthodoxy. Of course the rejection of Platonic type of mysticism was traditional practice for the Fathers. But what the Fathers of this Council were completely shocked at was Barlaam's claim that God reveals His will by bringing into existence creatures to be seen and heard and which He passes back into non existence after His revelation has been received. One of these supposed creatures was the Angel of The Lord Himself Who appeared to Moses in the burning bush. For the Fathers of the Ecumenical Councils this Angel is the uncreated Logos Himself. (See John S. Romanides, Underlying Positions of This Website.)

- ^ Jugie, Martin (1940) "Barlaam, est-il ne catholique?." Échos d'Orient, 39 (197) : 100-125. Available on-line at: Persee.fr

- ^ a b c d Saint Gregory Palamas (1999). Dialogue Between an Orthodox and a Barlaamite. Global Academic Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 9781883058210.

- ^ Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 1999. p. 836.

Hagioritic Tome Palamas.

- ^ a b c "Gregory Palamas: An Historical Overview". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ 1. His teaching about the light on Mt. Tabor, which he claimed was created. 2. His criticisms of the Jesus Prayer, which he accused of being a practise of the Bogomils; also charged it with not proclaiming Christ as God. Gregory Palamas: Historical Timeline, Appendix I: Timeline: Barlaam and the Councils of 1341 from Baron Meyendorff "Monachos.net - Gregory Palamas: Historical Timeline". Archived from the original on 2012-06-07. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ^ a b Palamas, Saint Gregory; Meyendorff, John (1983). Gregory Palamas. Paulist Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780809124473.

- ^ "accusing Gregory Palamas of Messalianism" (Antonio Carile, Η Θεσσαλονίκη ως κέντρο Ορθοδόξου θεολογίας -προοπτικές στη σημερινή Ευρώπη (Thessaloniki 2000, pp. 131-140), English translation provided by the Apostoliki Diakonia of the Church of Greece).

- ^ NOTES ON THE PALAMITE CONTROVERSY and RELATED TOPICS by John S. Romanides The Greek Orthodox Theological Review, Volume VI, Number 2, Winter, 1960-61. Published by the Holy Cross Greek Orthodox Theological School Press, Brookline, Massachusetts.[1]

- ^ Parry (1999), p. 231

- ^ 1. His teaching about the light on Mt. Tabor, which he claimed was created. 2. His criticisms of the Jesus Prayer, which he accused of being a practise of the Bogomils; also charged it with not proclaiming Christ as God. Gregory Palamas: Historical Timeline Appendix I:Timeline: Barlaam and the Councils of 1341 from Baron Meyendorff "Monachos.net - Gregory Palamas: Historical Timeline". Archived from the original on 2012-06-07. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ^ John Meyendorff. Byzantine Theology: Historical trends and doctrinal themes (Fordham University Press; 2nd edition, 1983, ISBN 978-0-8232-0967-5).

- ^ a b c Runciman, Steven (1986). The Great Church in captivity: a study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the eve of the Turkish conquest to the Greek War of Independence. Cambridge University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9780521313100.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 815

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 923

- ^ Laiou, Angeliki (2008). "Chapter II.3.2D: Political-Historical Survey, 1204–1453". In Jeffreys, Elizabeth; Haldon, John; Cormack, Robin (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-19-925246-6.

- ^ "Gregory Palamas: Historical Timeline". Archived from the original on June 7, 2012.

- ^ "Tradition in the Orthodox Church". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ^ Jugie, Martin (13 June 2009). "The Palamite Controversy". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ^ a b c Jugie, Martin (13 June 2009). "The Palamite Controversy". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ^ Jugie, Martin (13 June 2009). "The Palamite Controversy". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ^ Crisis in Byzantium: The Filioque Controversy in the Patriarchate of Gregory II of Cyprus (1283-1289). St Vladimir's Seminary Press. 1997. p. 205. ISBN 9780881411768.

- ^ "Russian Orthodox encyclopedia, article on Gregory Palamas".

- ^ Kyiv Triodion. 1620.

- ^ a b Simon, Marincak. The Sources and Resources of the Carpathian Byzantine Liturgical Tradition of the Eparchy of Mukačevo.

- ^ Acts of Synod of Zamoiske, chapter 17.

- ^ Zhukovskyi, Viktor (2018). СВЯТИЙ ГРИГОРІЙ ПАЛАМА І ЙОГО ЛЕГІТИМІЗАЦІЯ В УГКЦ [Saint Gregory Palamas and His Legitimization in the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church] (in Ukrainian).

- ^ "St. Gregory Palamas". Melbourne: Eparchy of Saints Peter and Paul of Melbourne. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Calendar of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (in Ukrainian)".

Sources

[edit]- Russell, Norman (2019). Gregory Palamas and the Making of Palamism in the Modern Age. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-964464-3.

Further reading

[edit]- A Study of Gregory Palamas (ISBN 0-913836-14-1) By John Meyendorff Translated by George Lawrence (1964)

- St. Gregory Palamas and Orthodox Spirituality (ISBN 0-913836-11-7) by Fr. John Meyendorff

- Saint Gregory Palamas as a Hagiorite (ISBN 960-7070-37-2) by Metropolitan Hierotheos (Vlachos) of Nafpaktos

- Introduction to St. Gregory Palamas (ISBN 1-885652-83-6) by George C. Papademetriou

- Triune God: Incomprehensible but Knowable—The Philosophical and Theological Significance of St Gregory Palamas for Contemporary Philosophy and Theology edited by Constantinos Athanasopoulos, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015 (ISBN 978-1-4438-8055-8)

- Orthodox Mysticism and Asceticism: Philosophy and Theology in St Gregory Palamas’ Work ed. by C. Athanasopoulos, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020.

- “The influence of Ps.Dionysius the Areopagite on Johannes Scotus Eriugena and St. Gregory Palamas: Goodness as Transcendence of Metaphysics”, by C. Athanasopoulos, in Agnieska Kijewska, ed., Being or Good? Metamorphoses of Neoplatonism, Lublin: Catholic University of Lublin Press (KUL), 2004, pp. 319–341.

- “Scholastic and Byzantine Realism: Absolutism in the Metaphysics and Ethics of Aquinas, Duns Scotus, Ockham and the critique of St. Gregory Palamas”, by C. Athanasopoulos, in Verbum (the official Journal of the Institute of Medieval Philosophy, Department of Philosophy, University of St. Petersburg, Russia), Vol. 6, Volume Topic: Aristotle in Medieval Metaphysics, January 2002, pp. 154–165.

- ‘St. Gregory Palamas, (Neo-)Platonist and Aristotelian Metaphysics: the response of Orthodox Mystical Theology to the Western impasse of intellectualism and essentialism’ by C. Athanasopoulos in Divine Essence and Divine Energies: Ecumenical Reflections on the Presence of God in Eastern Orthodoxy, edited by C. Athanasopoulos and C. Schneider, James Clarke & Co, April 2013. (ISBN 9780227173862), pp. 50–67.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). "Gregory Palamas". The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Vol. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1560. ISBN 0195046528.

External links

[edit]- St Gregory Palamas Orthodox Icon and Synaxarion

- International Conference on St Gregory Palamas, Thessaloniki 2012 with links to abstracts and reports from the Conference

- Papers from the International Conference on St Gregory Palamas (Thessaloniki, Veroia and Mt Athos, 2012)

- Palamas Seminar Meetings

- Papers from the International Conference on Mysticism and Asceticism in St Gregory Palamas (Veroia 2015)

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes

- Light for the World: the Life of St. Gregory Palamas (1296–1359) by Fr. Bassam A. Nassif

- An Overview of the Hesychast Controversy

- Melkite Greek Catholic Information Centre on St. Gregory Palamas

- Excerpt from "Byzantine Theology, Historical trends and doctrinal themes" by John Meyendorff

- Gregory Palamas at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- 1296 births

- 1359 deaths

- 14th-century Christian saints

- 14th-century Byzantine monks

- 14th-century Byzantine bishops

- 14th-century Byzantine writers

- 14th-century Christian mystics

- 14th-century Eastern Orthodox theologians

- Athonite Fathers

- Byzantine bishops of Thessalonica

- Byzantine Christian mystics

- Byzantine saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- Byzantine theologians

- Eastern Catholic saints

- Eastern Orthodox archbishops

- Eastern Orthodox mystics

- Eastern Orthodox saints

- Eastern Orthodox theologians

- Greek Christian monks

- Greek Christian mystics

- Greek theologians

- Medieval Athos

- Medieval Thessalonica

- People from Constantinople

- Saints of medieval Greece

- Saints of medieval Macedonia

- 14th-century Greek musicians

- 14th-century Greek writers

- 14th-century Greek educators

- 14th-century Greek philosophers

- Palamism

- Hesychasts

- People associated with Vatopedi

- People associated with Great Lavra

- Philokalia